Vietnamese Imperial Attire Of The Le Dynasty: The Standardization Of Ritual And Regalia

Following the Lam Sơn Uprising and the establishment of the Later Le Dynasty in 1428, the state laid the foundation for a nation where Confucianism became the principal political and social ideology. In this context, court attire evolved into the paramount symbol of power and ritual hierarchy. From the Emperor’s magnificent Cổn Miện set to the official robes of the mandarins, every detail distinctly reflected a strict social order based on rank and the concept of the Heavenly Mandate.

1. Attire of the Le Emperors

1.1. Ceremonial and formal attire

During Grand Court Assemblies and crucial state rituals, such as the Sacrifices to Heaven and Earth (tế Giao), ancestral rites (tế Miếu), or the Lunar New Year, the Emperor wore the Cổn robe and the Mũ Miện. This was the highest-grade attire, embodying the Heavenly Mandate and the connection to the cosmos through its intricate symbolic patterns.

During the Early Le period, the Cổn Miện set was reserved exclusively for these supreme rituals and did not feature in routine court business

“The Cổn Miện set of the Son of Heaven from the Ly and Tran dynasties cannot be verified… Our country’s subsequent dynasties lacked definitive traces of the Cổn Miện set until Emperor Le Thai Tong first established the Mũ Miện, but later generations discontinued its use. From the Restored Le Dynasty (Le Trung Hung) onward, the Emperor only wore the Xung Thiên hat for great ceremonies.”

Phan Huy Chu

1.2. Daily Attire: The imperial robe and Xung Thiên hat

In the Early Le period, for routine political activities, including the first and fifteenth days of each lunar month, the familiar image of the Emperor was the Imperial Robe paired with the Xung Thiên hat. However, by the time of the Restored Le Dynasty (Le Trung Hung), this ensemble had been elevated to the Emperor’s Formal Court Attire.

The imperial robe of the Early Le Emperors belonged to the đoàn lĩnh (also known as viên lĩnh or cổ kiềng) style, featuring wide, loose sleeves, worn over a giao lĩnh inner robe. Its design remained largely unchanged compared to previous dynasties. The patterns on the robe typically featured coiling dragons on both shoulders and the abdomen area, inheriting the dragon style of the Ly – Tran Dynasties but also influenced by the dragon motifs of the early Ming Dynasty in China.

Portrait of Emperor Lê Thánh Tông

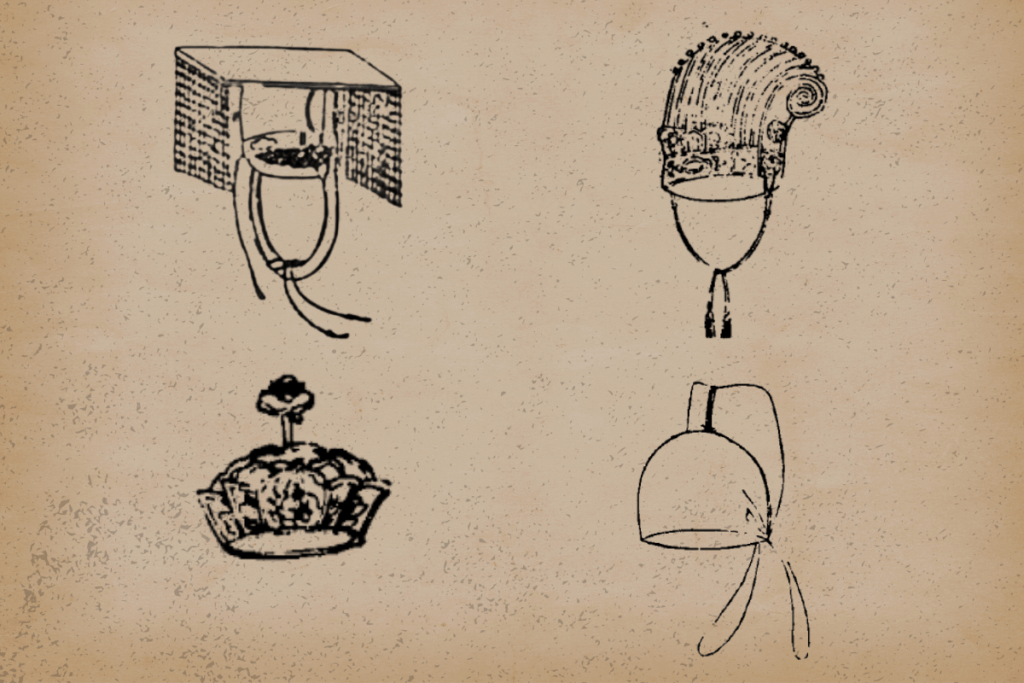

Xung Thiên hat and Imperial Robe from the Early Le Dynasty

The Xung Thiên hat (literally “Hat Reaching Heaven”—a variant of the Phốc Đầu hat, also called Dực Thiên hat) was distinguished by its two “wings” extending upward instead of horizontally, as seen on the standard Phốc Đầu. This hat was typically worn when the Emperor held court, projecting a solemn demeanor that differentiated it from the purely ritualistic Mũ Miện. The pairing of the Imperial Robe and Xung Thiên hat created a majestic yet practical appearance, suitable for the Routine Court Assemblies, where the Emperor directly managed state affairs.

Xung Thiên hat from the Nguyen Dynasty

Xung Thiên (Dực Thiện) hat of Ming Emperor Shenzong

2. Attire of Civil and Military Mandarins

2.1. Official and Formal Attire

Mandarins’ attire during the Early Le Dynasty was rigorously standardized, clearly reflecting the Confucian emphasis on social hierarchy within the court.

During court sessions, officials wore the Phốc Đầu hat and a ceremonial robe. The form of the Phốc Đầu evolved: early 15th-century wings were narrow, while by the late 15th century, the wings were wider, creating a more dignified presence. The robe colors were strictly mandated by rank: red for the third rank and above, green for mid-level officials, and blue for lower-ranking officials

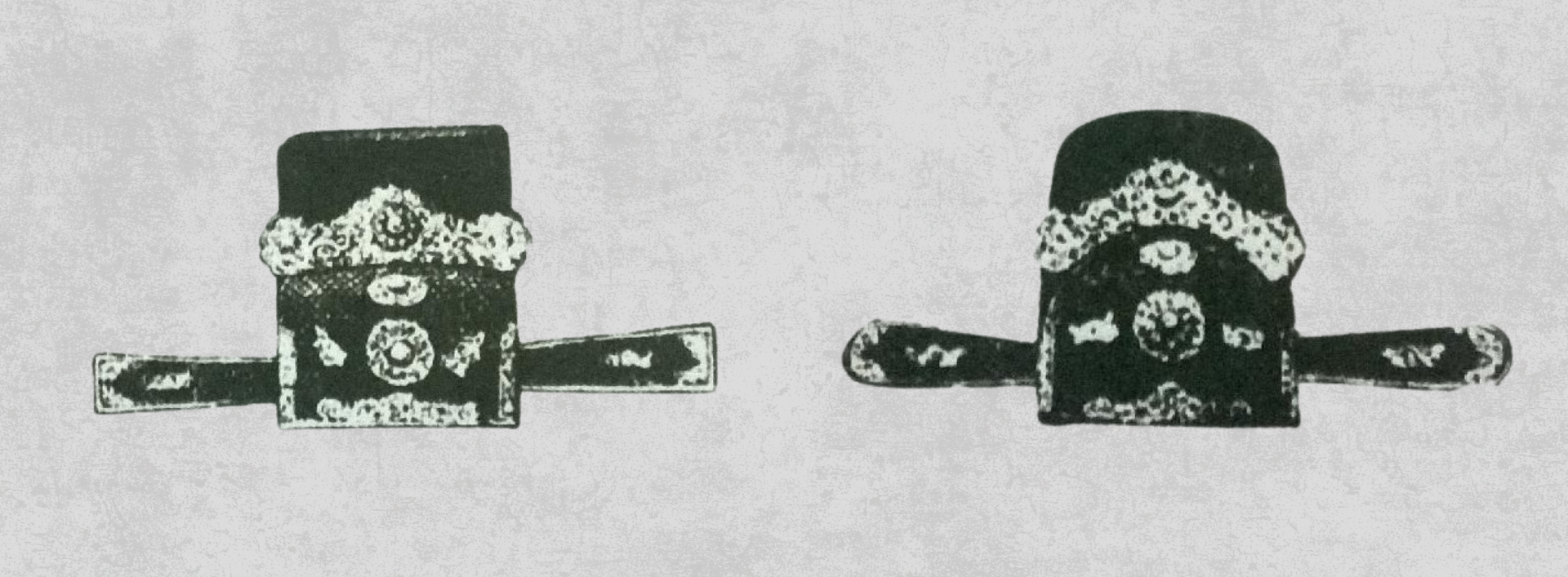

Phốc Đầu hat featuring two long, narrow wings, characteristic of the Song Dynasty style

Phốc Đầu hats worn by Military and Civil officials of the Nguyen Dynasty

2.2. Daily Attire

For Routine Court Assemblies, mandarins wore the Ô Sa hat alongside the Đoàn Lĩnh robe (a round-collared robe). In 1486, Emperor Lê Thánh Tông even decreed that the hat wings must angle slightly forward, emphasizing uniformity and solemnity in the court dress.

A significant defining feature of the Early Lê official system was the adoption of the Bổ tử (Mandarin Square) starting in 1471. This was a square piece of embroidered fabric attached to the front and back of the robe, serving as an immediate indicator of rank. Civil officials used bird motifs, while military officials used animal motifs. Notably, a distinctly Vietnamese element was expressed in the design for military officials of the sixth rank and below, who used the elephant motif—a familiar symbol of Daiviet—differing from the regulations of the Ming Dynasty.

Round-shaped Ô Sa hat of the Ming Dynasty

The Ô Sa hat in the portrait of Nguyen Trai

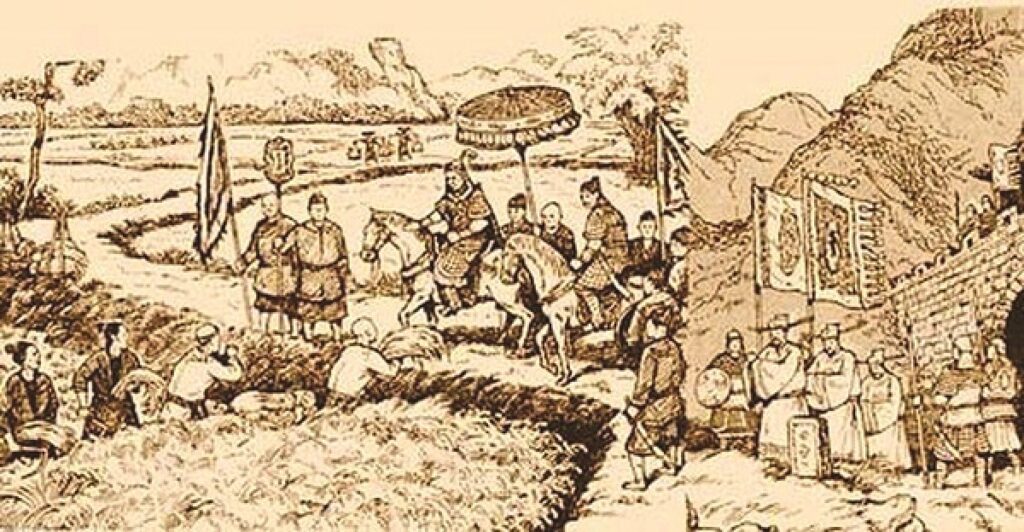

An Nam mandarins in Daily Court Attire, as depicted in three variants of the Huang Qing Zhigong Tu

Mandarin Squares featuring the Crane (for civil officials) and the Qilin

The imperial attire of the Early Le Dynasty established a level of ritual and standardization unprecedented in previous eras. The image of the Emperor in his yellow Imperial Robe and Xung Thiên hat, flanked by mandarins in their Phốc Đầu and Ô Sa hats with embroidered Bổ tử squares, illustrated a social order meticulously governed by ritual. This system of imperial and official wear not only reflected Confucian ideology but also became a lasting foundational influence on the court attire of subsequent dynasties.